By: Tristan Finn

The Historic Sites Act of 1935 marked the first time in our Nation’s history the federal government declared the preservation of historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significance for use of the public as national policy. [i] While the symbolic importance of this act may not be understated, the original intentions of preservation were largely replaced by the needs and desires to rapidly industrialize this nation until National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) was passed in 1966. [ii] Passed with the intention of “insur[ing] future generations a genuine opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the rich heritage of our Nation,” the NHPA refocused the Nation’s attention towards preserving historical landmarks, leading to the passing of several important preservation measures, including the Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) and the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). [iii]

This act has been widely successful in maintaining several historic landmarks, evidenced by the nearly 90,000 listings added to the NRHP and the $117 billion in private investment contributed through the Historic Tax Credit; however, the number of historic landmarks is arguably far too great for this act to adequately protect them all. [iv] Luckily, states have taken the initiative to fill in these protective gaps left by the act. [v] California, a prime example of the states’ willingness to preserve these historic landmarks, has recently passed the California Drought, Water, Parks, Climate, Coastal Protection, and Outdoor Access for All Act of 2018, which involved over $37 million in funding being directed towards preserving natural, cultural, historic, park, and community resources,. [vi] Other states have taken a slightly different approach to the preservation of landmarks and historic sites. [vii] For example, Kentucky has employed an incentive-based approach to preserving historic landmarks. [viii] In addition to ranking twelfth nationally for use of tax credits provided through the HPF, Kentucky has also employed its own tax credit, the Kentucky Historic Preservation Tax Credit, which has been used in tandem with the federal Historic Tax Credit to great effect. [ix] While such a method arguably places a smaller burden on the Kentucky taxpayer, some historic landmarks have slipped through the cracks. [x]

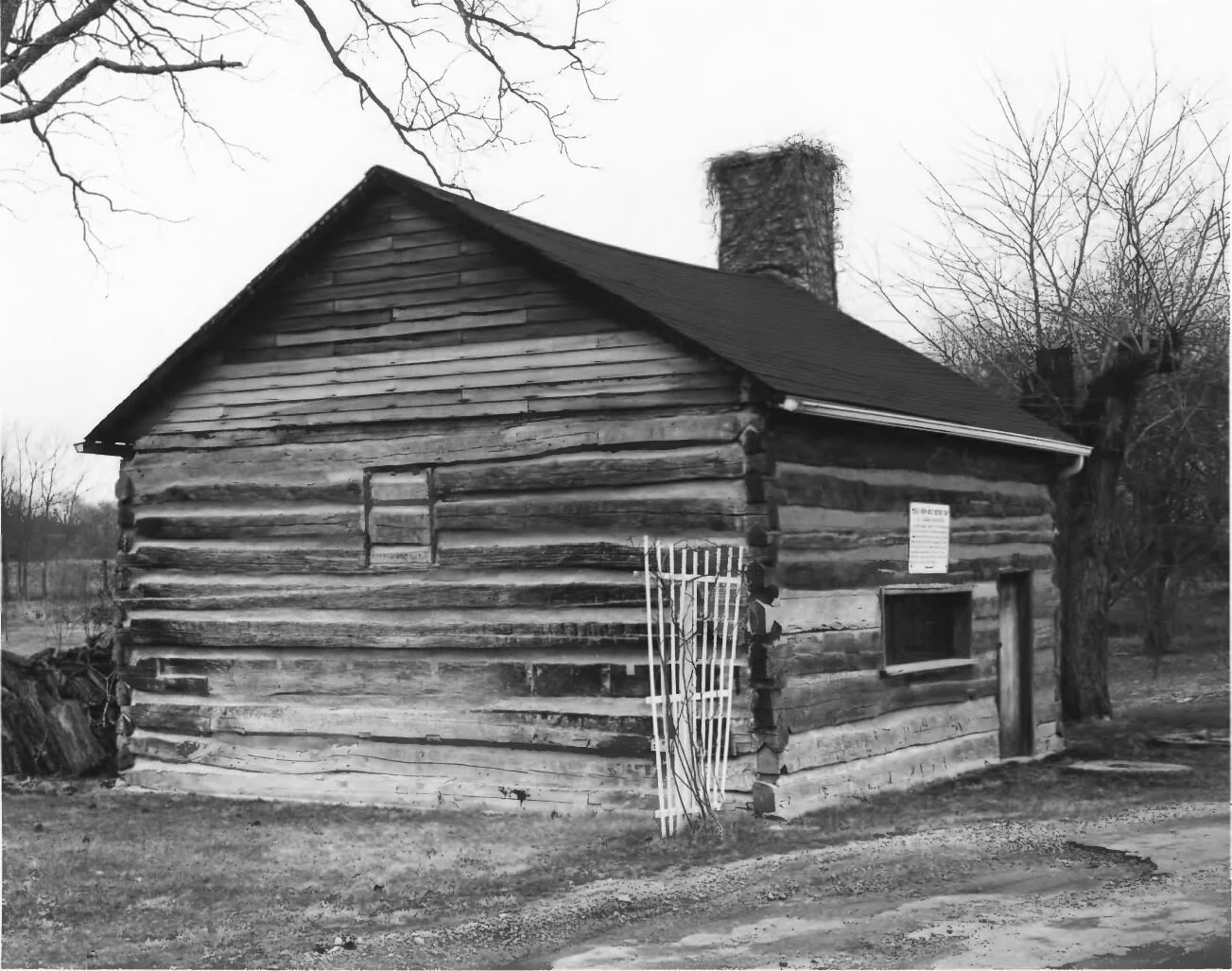

A prime example of this slippage is the NRHP-recognized house built by Capt. James Wright in 1791. [xi] Due to no longer being able to use or reasonably afford this house and its adjacent NRHP-recognized cabin on two acres of land, the current owner sought to sell the house under the foreboding reality that he might have to demolish it if he could not find a buyer in time. [xii] The owner has been searching for a buyer since mid-2018, which suggests that the fate of his historic landmark is still undecided. [xiii]

Credit: https://goo.gl/maps/tVmFRgtMAC9v2Rho7

The problem with Kentucky’s method of preserving the fate of historic landmarks is quite clear. When the reliance of preservation is placed on the individual, such preservation may easily fail once that individual finds the incentives of using, preserving, and maintaining the landmark no longer outweigh the associated costs. This method essentially relies on the continued personal benefits exceeding the costs of the property, as it is unreasonable to believe individuals will continue to act against their own self-interest. However, even if one individual may find a historic landmark to no longer be to their benefit, the collective public may disagree. [xiv] The 1885 Barnes House in Mt. Washington, Kentucky has proven that benefits assessed by the public may not only be present, but also important enough to supplant the preservation responsibilities commonly placed upon individuals. [xv] Through the creation of a GoFundMe page and various other local means of collecting funds, Bullitt County has proven that the public may successfully fight for preservation of historic landmarks. [xvi]

Such communal efforts may not always be relied upon. This is particularly true for examples like the Capt. James Wright House and Cabin, as unlike the Barnes House, the Wright House has been predominately marketed as a new home intended for use by an individual; and due to its current need for significant renovation, the house would likely not be viewed as an asset to surrounding public. [xvii] This issue presents all the more reason for the state to step in. Whenever such a landmark is in need of repair and whenever such a landmark does not have the community needed to support it, who or what else may preserve such landmarks other than the government?

While arguments might be made ad nauseum over the inherent value and benefits such landmarks confer to the public, we must never forget why the legislation created these tools for historic preservation. They not only identify what is and what is not beneficial to the collective public, but they allow our future generations the opportunity to see those benefits for themselves. [xviii]

[i] Historic Sites Act of 1935, 16 U.S.C. § 461 (1935).

[ii] Federal Historic Preservation Program, NCSHPO, https://ncshpo.org/resources/federal-historic-preservation-program/ (last visited Feb. 5, 2020).

[iii] Id.; Section 1 of the National Historic Preservation Act, Pub. L. No. 89-665, as amended by Pub. L. No. 96-515; National Register of Historic Places, NCSHPO, https://ncshpo.org/resources/national-register-of-historic-places/ (last visited Feb. 5, 2020).

[iv] Historic Preservation Fund - Brief Overview, NCSHPO, https://ncshpo.org/issues/historic-preservation-fund/ (last visited Feb. 5, 2020).

[v] California Natural Resource Agency, Sierra Fund a CA Natural Resources Agency Grant Recipient for the Nisenan Preserve, YubaNet (Oct. 3, 2019, 1:15 PM), https://yubanet.com/regional/sierra-fund-a-ca-natural-resources-agency-grant-recipient-for-the-nisenan-preserve/.

[vi] Id.

[vii] See State Historic Preservation Office, Historic Rehab Tax Credits, Kentucky Heritage Council (2017), https://heritage.ky.gov/historic-buildings/rehab-tax-credits/Pages/overview.aspx.

[viii] See id.

[ix] Id.

[x] See Tom Eblen, Patriot Built This House in 1791. If it Doesn't Sell Soon, Owner May Demolish it. Lexington Herald Leader (June 20, 2018, 10:42 AM), https://www.kentucky.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/tom-eblen/article213435634.html.

[xi] Id.; Nat’l Park Serv., https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/76000846 (last visited Feb. 5, 2020).

[xii] Supra note x.

[xiii] realtor.com, https://www.realtor.com/realestateandhomes-detail/4090-Lexington-Rd_Paris_KY_40361_M41366-24457 (last visited Feb. 5, 2020).

[xiv] Jennifer Baileys, Developers Want to Take Down Barnes House, WLKY (Oct. 31, 2017, 6:45 PM), https://www.wlky.com/article/developers-want-to-take-down-barnes-house/13130052.

[xv] See id.

[xvi] Supra note x.

[xvii] See id.

[xviii] Section 1 of the National Historic Preservation, supra note iii.